Distribution and Population Density of

Moustached Tamarins on Padre Isla

During the course of the investigation 123 moustached tamarins residing in 17 social groups were encountered on the island. We concentrated our efforts on 16 of these groups and trapped, marked, and released 98 of the 114 animals (86%) associated with these 16 groups.

Twenty-six of the animals captured (26%) in 1990 had been captured and tattooed during previous field seasons. For many of these individuals we were able to reconstruct a history of previous group affiliation, previous group partners, and migratory activities. Ten of the tamarins captured were original inhabitants of the island. Five of these were males and five were females. Nine of these "founders" (4 males and 5 females) were released as adults, and thus were at least 12 years of age when recaptured in 1990. All five of these female founders were reproductively active in 1981, and at least two (#603 and #479) continued to be reproductively active in 1990. One of these 12 + year old females was simultaneously lactating and pregnant during our study.

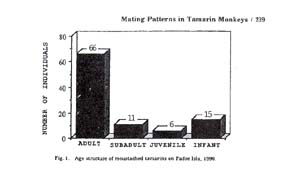

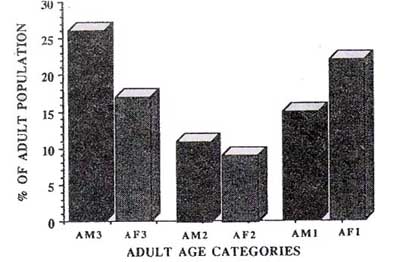

The demographic structure of the moustached tamarin population on Padre Isla is presented in Figure 1. The animals trapped included 66 adults, 11 subadults, 6 juveniles, and 15 infants. The ratio of adults to immatures was 2:1, and the number of males and females was approximately equal (1.02:1). Of 31 adult females examined, "1 (22.5%) were pregnant and 7 (22.5%) were lactating. Using dental wear as an indicator of the age structure of the adult population, 38% of the tamarins were classified as young adults (Al), 18% as middle-aged adults W), and 44% as oldest adults W) (Fig. 2). The population density of moustached tamarins, on the island is 26 ind/km2.

Fig. 1. Age structure of Moustached tamarins on Padre Isla, 1990,

Group Size and Composition

Based on a sample of 13 groups in which all or all but one member was trapped, mean group size was 7, including 2.2 adult males and 2.0 adult females (Table D.

The largest bisexual group contained 11 animals, and the smallest bisexual group. contained 4 animals. The number of adult males in these groups ranged from 1-3, and the number of adult females ranged from 1-4. None of the 13 groups was characterized by a single adult male-female pair.

Age Structure of the Island Population

Using dental wear as an indication of relative age, and assuming that males and females wear their dentition at equal rates, there were considerably more A3 (oldest) males in the population (27% of adults) than A3 females (15% of adults) (Figure 2). Although this disparity is not statistically significant (x2 = 1.6; d.f. = 1; P > .05), and could reflect sampling error or short-term perturbations in males female sex ratios at birth, there is some indication that competition for a limited, number of breeding opportunities may contribute to increased female dispersal, and possibly increased female mortality. Despite the fact that direct acts of aggression between females residing in the same group are infrequent, none of the 13~, social groups contained more than I A3 or I A2 female (Table II). Apparently females of these older age categories are intolerant of age mates and exclude them from cohabiting in the same social group. This is in marked contrast to the behavior of adult males. Thirty-eight percent of the groups on Padre Isla were composed of either 2 A3 or 2 A2 males.

Fig.2, Adult age composition of moustached tamarins on Padre Isla, 1990.

TABLE I. Size and Composition of 13 Moustached

| Group |

Adult males

|

Adult females

|

Group size

|

| Orange 1 |

2

|

2

|

6

|

| Silver 1 |

2

|

2

|

6

|

| Rosado 1 |

3

|

4

|

11

|

| Copper 2 |

1

|

3

|

5

|

| Green 2 |

3

|

1

|

6

|

| Red 3 |

3

|

3

|

11

|

| Celeste 3 |

3

|

2

|

6

|

| Blue 3 |

2

|

1

|

4

|

| Brown 3 |

2

|

2

|

9

|

| White 3 |

2

|

1

|

6

|

| Purple 3 |

2

|

2

|

9

|

| Beige 4 |

2

|

1

|

4

|

| Orange 4 |

2

|

2

|

8

|

| Total |

29

|

26

|

91

|

| Mean |

2.2

|

2

|

7

|

In virtually all of the groups censused, it is the oldest

female that breeds (see below). Our records indicate that 78% of the A3 females

and 67% of the A2 females were either pregnant or lactating at the time of capture.

In contrast only 21% of the Al females were pregnant or lactating. Young adult

females on Padre Isla rarely produce offspring. Two groups provide exceptions.

In the Rosado 3 group (not listed in Tables I and 11 because more than I group

member was not trapped), the A3 female died in August and the lone remaining

Al female became pregnant in September. The blue group was the other social

unit characterized by a single young adult breeding female. She was the only

female in her group and was observed nursing a single infant. This group of

four was the smallest bisexual group on the island. We have no examples from

the 1990 trapping period of groups with more than I adult female in which only

the youngest female was reproductively active.

TABLE II. Age Structure of Adult Group Members in Moustached Tamarins, Padre Isla, Peru 1990

| Group |

Adult males

|

Adult females

|

||||

|

A3

|

A2

|

A1

|

A3

|

A2

|

A1

|

|

| Orange 1 |

2

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

| Silver 1a |

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Rosado 1 |

0

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

| Copper 2 |

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

| Green 2 b |

0

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Red 3 |

2

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

| Celeste 3 |

2

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

| Blue 3 |

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

| Brown 3 |

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

| White 3 |

0

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Purple 3 |

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

| Beige 4 |

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

| Orange 4 a |

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

| Total c |

14

|

7

|

7

|

8

|

5

|

11

|

| Total d |

18

|

7

|

7

|

11

|

6

|

13

|

a A lactating female in this group was observed but

not examined.

b An adult male in this group was observed but not examined.

c Groups in which more than 1 member was not trapped are omitted

from these calculations.

d Data from all 16 groups

Although there was no evidence that more than I female in a group was lactating or had recently given birth, 23% (3/13) of the complete groups contained either 2 pregnant or I pregnant and I lactating female. In each case, these were among the largest groups in the population, averaging 10 animals per group. These groups were also similar in that it was an A3 female that was lactating/ pregnant, and an A2 female that was pregnant but not lactating. These data suggest that when groups size exceeds 9, the ability of the older dominant female to suppress ovulation and reproductive activities in a younger subordinate female is significantly diminished. Although we cannot discount the possibility that in groups with 2 reproductively active females, one of the females was a recent migrant and entered the group already pregnant, given that only I female in a group gives birth (we have no evidence of more than 1 lactating female in any group), reproductive competition in these females appears to result in abortion, expulsion, or group fissioning.

Body Size and Reproductive Activity

In an attempt to determine whether particular body measurements were correlated with reproductive sovereignty or reproductive condition, we compared body weight, crown-rump length, genital size, nipple length, and suprapublic gland size among adult females. The results (Table 111) indicate that A3 females are not significantly heavier, longer, or characterized by larger genitalia than either Al Or A2 females. Differences in the size of the suprapublic gland between U and Al females were statistically Significant (t = 2. 10; P < .05), however, and gland area may provide a general measure of distinguishing older and/or reproductively active females from younger and nonreproductive females. The suprapublic gland, which is reported to play an important role in socio-sexual behavior and perhaps reproductive suppression [Snowdon & Soini, 1988], averaged 2.82 cm2 in A3 females, 2.35 CM2 in A2 females, and 2.03 cm2 in A1 females. In only 1 group, in our sample was the area of the suprapublic gland larger in a nonreproductive female than in a reproductive (pregnant or lactating) female.

TABLE Ill. Body Size Measurements of Adult Male and Female

Moustached Tamarins, Padre Isla, 1990

|

Adult females

|

|||

|

A3

|

A2

|

A1

|

|

|

(N = 10)

|

(N = 6)

|

(N = 13)

|

|

| Body weight |

585.3

|

564.1

|

560.8

|

| (grams) |

+55

|

+56

|

+42

|

| Body length |

239

|

245

|

239

|

| (cm) |

+7.8

|

+6.8

|

+9.9

|

| Vulva area |

3.69

|

3.44

|

3.23

|

| (mm 2) |

+1

|

+1

|

+1.1

|

| Gland area |

2.82**

|

2.35

|

2.03

|

| (mm 2) |

+0.97

|

+0.72

|

+0.74

|

| Nipple length a |

3.66*

|

1.67

|

1.8

|

| (mm) |

+0.92

|

+0.43

|

+0.89

|

|

|

Adult males

|

||

|

A3

|

A2

|

A1

|

|

|

(N = 18)

|

(N = 6)

|

(N = 6)

|

|

| Body weight |

567.5

|

544.6

|

550.4

|

| (grams) |

+75

|

+34

|

+36

|

| Body length |

243

|

243

|

243

|

| (mm) |

+7.4

|

+6.9

|

+5

|

| Testes volume b |

6.87

|

5.91

|

4.78

|

| (mm 2) |

+2.9

|

+2.9

|

+1.4

|

*Lactating females were exduded from the calculations. Sample

size includes 6 A3 females, 5 A2 females, and 11 A1 females.

bTestes volume was calculated using the equation

Vol = 3.14 (xy 2)/6. X, testes length; y, testes width.

*Significantly greater in Adult 3 females than in either

A2 or Al females (P < .001).

**Significantly greater in Adult 3 females than in Al females

(P < .05).

Data on nipple length in nonlactating moustached tamarin females provide additional support for the contention that older adult females are the principal breeders. Mean nipple length in A3 females was 3.6 mm. In A2 and A1 females nipple length was 1.5 min and 1.8 min, respectively (Table III). Differences between A3, A2, and Al females were significant (P = .001). If nipple size is an indication of previous breeding activity, it appears that in this population A2 females were not significantly more likely to have reproduced successfully than A1females.

A similar analysis of body measurements in mate moustached

tamarins (Table IV).

TABLE IV. Age and Sex Status of Solitary Migrant

Moustached Tamarins on Padre

Isla, 1981-1982

|

Adult male

|

Subadult male

|

Adult female

|

Subadult male

|

Total no. trapped

|

|

| 1981 |

5

|

2

|

4

|

0

|

27

|

|

4 1% of animals trapped were solitary migrants

|

|

||||

| 1982 |

1

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

29

|

|

14% of animals trapped were solitary migrants

|

|

||||

| TOTAL |

6

|

2

|

6

|

1

|

56

|

III) failed to indicate significant differences in body weight,

body length, and testes volume (male moustached tamarins rarely scent mark and

have poorly developed suprapubic glands, which are difficult to measure). Based

on these body measurements, there was no evidence that any particular age class

of adult males had a reproductive advantage or was in better reproductive condition

than any other adult age class.

Patterns of Migration

Field data on several tamarin species indicate that migration is common, and that adults and subadults of both sexes transfer into and out of groups. This same pattern appears to characterize the moustached tamarin population on Padre Isla. Our findings indicate that after their initial introduction onto the island, groups underwent a period of instability. There are several cases in which each of 3 or 4 adults from the same founding group in 1980 individually joined animals from different social groups by 1981. Although the censuses in 1981 and 1982 do not allow us to calculate precise rates of migration or identify the effects of mortality on group stability, one year after being released on the island 43% of the adults/ subadults recaptured had transferred as individual migrants into a new social group (Table IV). These migrants included adult and subadult males, as well as reproductively active and reproductively inactive adult females Data from the 1982 census in6cate that although immigration and emigration were still common, group composition was considerably more stable. Fewer individuals migrated alone (14%), although both adult males and adult females continued to be the principal migrants (Table IV).

Combining the census data collected by the PPP between 1980 and 1989 with our most recent trap census in 1990, we were able to identify a set of migration patterns that are recurrent and appear to characterize this moustached tamarin population. These patterns can be distinguished from other migratory events that occur rarely, if at all. It must be emphasized that the data base used in these reconstructions has several important limitations. Not all of the groups trapped over the 10 year period represent complete groups, there are significant gaps in life histories of most animals, especially between 1983 and 1987, when only a small proportion of the tamarin population was trapped and tattooed, and in 1986, 29 animals were removed from the island for captive study. Although these problems force us to qualify many of our conclusions and prohibit statistical treatment of the data, a number of common migratory patterns can be identified. These are described as follows:

1. Individual migrations of adult and subadult females.

These include both nulliparous and multiparous females.

2. Individual migration of adult and subadult males.

These include males of all adult age categories.

3. A large established group splitting into 2 smaller bisexual

groups. One of these groups remains in the original range and the other, a more

transient group, eventually joins another small social group.

4.

Two adult/subadult males migrating together into the same social group. We have

8 unambiguous examples of male-male dispersal. In one case, the migrants were

twin A1 brothers. In 2 additional cases the males were of the same age class

but of unknown genealogy (1 pair of subadults and 1 pair of A1 males). In 3

of the remaining cases the paired migrants were of different age classes (A3/Al

or A/SA). Our data indicate that these migrants have remained together in their

new social group from 4 to over 8 years.

5. Absence of identifiable cases of 2 adult and/or subadult

females migrating together into the same social group. We did, however, encounter

a stable group of 3 adult females that after a period of several months was

joined to 2 immigrant males.

6. An adult offspring remaining in the same group as its

mother We have 2 unambiguous cases of fully adult offspring remaining in their

natal group. In the first instance, a 3-year-old female continued to reside

in the same group as her A3 mother. Neither female was pregnant or lactating

at the time of capture. In the second example, an adult male has remained in

the same breeding group as his mother for a period of 8 years. His mother remains

the dominant/breeding female of the group. We have no evidence of whether or

not her son is reproductively active. At present our data base is insufficient

to identify how many of the young adults in the population are offspring of

other adults in their group, and the degree to which adult offspring care for

younger siblings.

Mating Activities

During the 1990 field season we also conducted a detailed 6 month investigation of mating behavior and social interactions in 2 marked moustached tamarin social groups. The copper group was composed of 3 adult females and 2 males (1 A3 male and 1 subadult) that had immigrated together into the group. The A3 male was observed to copulate with each of the group's 2 oldest females. The subadult male was observed to copulate only with the oldest female. Given that 2 males and 2 females in this group were sexually active and copulated during a time coinciding with the breeding season, the mating pattern of this group is provisionally described as polygynous (polygynandrous). Our second study group, the green group, consisted of a lactating A3 female, 3 adult males, and 2 infants. Four copulations were observed in the this group over a 5 day period One male copulated on 2 occasions and the other two males were each observed to copulate once. The mating pattern of this group is described as polyandrous During copulatory activities there was no evidence of increased levels of intrasexual aggression or behaviors generally associated with mate guarding or consort relationships in either group.