Interspecific Relations in a Mixed-Species Troop of Moustached Tamarins, Saguinus mystax, and Saddle-Back Tamarins, Saguinus fuscicollis (Platyrrhini: Callitrichidae), at the Rio Blanco, Peruvian Amazonia

ECKHARD W. HEYMANN

Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Kellnerweg 4, Göttingen, Federal Republic of Germany

This study examined the social interactions between moustached tamarins, Saguinus mystax, and saddle-back tamarins, Saguinus fuscicollis , living in a mixed-species troop at the Rio Blanco, Peruvian Amazonia, between July 1985 and July 1986. Mixed-species troops were common among the S. mystax and S. fuscicollis populations in the Rio Blanco study area; 72% of all sightings of S. mystax and 82% of all sightings of S. fuscicollis were in mixed-species troops (study group excluded from analysis). In the study group, the two species spent on average 82% of time in association. Interactions were observed at a rate of one per 5 h of observation. Most interactions (96%) were agonistic. About 70% of agonistic interactions occurred at small food resources (crown diameter < 5 m and/ or limited number of ripe fruits). Moustached tamarins were always dominant over saddle-back tamarins. Friendly interactions were extremely rare and were restricted to play invitations. Mutual calling was observed in the morning before the two species joined each other and during the day when they became separated. It is concluded that interspecific interactions and mutual calling incur some costs to the associated species but that these costs may be low.

Key words: Saguinus mystax, Saguinus fuscicollis , mixed-species troops, interspecific interactions

Received for publication April 27, 1989; revision accepted March 6, 1990.

Address reprint requests to Dr. E.W. Heymann, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Kellnerweg 4, 3400

Göttingen, Federal Republic of Germany

INTRODUCTION

Mixed-species troops (polyspecific associations) have been observed in both Old World and New World primates. In Africa, sympatric species of the genera Cercopithecus, Cercocebus, Colobus, and Procolobus frequently associate [e.g., Cords, 1987; Gautier-Hion, 1988; Struhsaker, 1981; Waser, 1980]. In the New World, mixed-species troops have been reported for Saimiri and Cebus [Baldwin & Baldwin, 1971; Podolsky, 1987; Terborgh, 1983], Saimiri and Cacajao [Bartecki & Heymann, 1987b; Mittermeier & Coimbra-Filho, 1982], and for sympatric tamarin species of the genus Saguinus (Table I). Some of these associations may occur by chance [Waser, 1982; Whitesides, 1989] but others bear biological significance for the associated species. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the function and benefits of mixed-species troops [for review see Struhsaker, 1981]. For associations of tamarins, the following three hypotheses seem to be particularly relevant [see Terborgh, 1983]: a) Enhanced detection and avoidance of predators. b) Joint defense of the territory and of food resources against neighboring troops [see also Garber, 1988a]. c) Enhanced feeding efficiency by avoiding visits to food trees that have already been exploited by one of the associated species. Mixed-species troops of tamarins have stable membership and are spatially cohesive and long-lasting temporally [cf., Garber, 1988a; Terborgh, 1983], but interspecific behavioral interactions generally seem to be rare. However, as Struhsaker [1981] pointed out, the way "different species tend to interact with each other could provide useful clues to the nature of their associations". For example, if species actively join each other, some benefit of associating may be anticipated [Terborgh, 1983]. The analyses of interspecific behavioral interactions might provide information on costs and benefits of mixed-species troops.

The present paper aims at providing quantitative information on the interspecific behavioral relations in a mixed-species troop of moustached tamarins, Saguinus mystax, and saddle-back tamarins, Saguinus fuscicollis . Particularly, the following questions are addressed: a) How do the two species interact with each other? b) Are the interspecific behavioral interactions related to ecological factors?

TABLE I.Mixed-species Troops in the Genus Saguinus

| Species |

A a

|

B b

|

Study site

|

References

|

| Saguinus mystax, |

58.3

|

_d

|

Rio Blanco

|

Castro and Soini [1978]

|

| Saguinus fuscicollis |

|

|

(NE-Perú)

|

|

|

52.9

|

69.2

|

Los Angeles

(NE-Perú) |

Glander et al. [1984]

|

|

|

0

|

0

|

Santa Cecilia

(NE-Perú) |

Glander et al. [1984]

|

|

|

100.0c

|

_d

|

Rio Yarapa

(NE-Perú) |

Ramirez [1984]

|

|

|

_d

|

_d

|

Río Blanco

(NE-Perú) |

Garber [1986,1988a,b]

|

|

|

72

|

81.8

|

Rio Blanco

(NE-Perú) |

This study

|

|

| Saguinus labiatus, |

75.9

|

59.5

|

Cobija

(N-Bolivia) |

Pook and Pook [1982]

|

| Saguinus fuscicollis |

_d

|

_d

|

Mucden

(N-Bolivia) |

Yoneda[1981,1984]

|

| Saguinus imperator |

100

|

100

|

Cocha Cashu

(SE-Perú) |

Freese et al. [1978]

|

| Saguinus fuscicollis |

-

|

-

|

Cocha Cashu

(SE-Perú) |

Terborgh (1983)

|

| Saguinus nigricollis, |

-

|

-

|

Puerto Leguizamo

|

Hernández-Camacho and

|

| Saguinus fuscicollis |

|

|

(S-Columbia)

|

Cooper (1976)

|

a A: Percentage Of sightings in which Saguinus

mystax, Saguinus labiatus, Saguinus imperator, or Saguinus nigricollis were

seen in association with Saguinus fuscicollis .

b B: Percentage of sightings in which Saguinus

fuscicollis was seen in association with Saguinus mystax, Saguinus

labiatus, Saguinus imperator, or Saguinus nigricollis.

c Based on trappings.

d No quantitative information available.

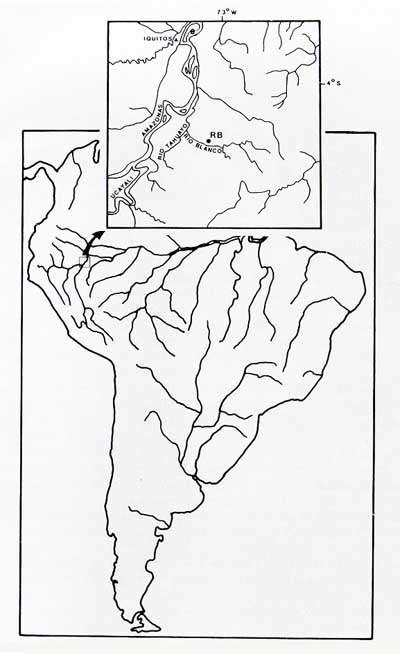

Fig. 1. Location of the Río Blanco study site (RB).

c) Do the two species actively join each other and by which mechanisms is this achieved? The results are discussed in relation to information on other mixed-species troops, especially in tamarins.