Frequency of mixed-species troops

Tamarin groups different from the study group were encountered on 29 occasions. This included five troops of known identity and three or four troops of unknown identity (Table II). Four of the five known groups were more frequently seen in mixed-species troops than in monospecific troops. In seven cases (24%) moustached tamarin groups, in four cases (14%) saddle-back tamarin groups, and in 18 cases (62%) mixed-species troops were observed. Thus 72% of all sightings of moustached tamarins and 82% of all sightings of saddle-back tamarins were in mixed-species troops. The formation of such mixed-species troops seems to be a general pattern in the populations of moustached and saddle-back tamarins of the study area.

Time Spent in Association

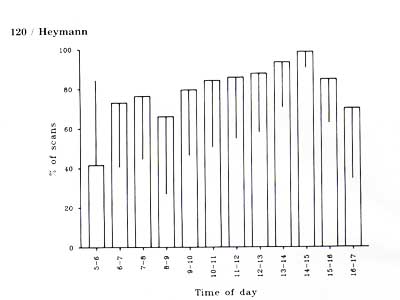

The moustached tamarin study group spent on average 82% (± 19%) of its activity time in association with the saddle-back tamarin group. Time of day significantly influenced the degree of association (F = 4.63, df = 11, N = 347, P < 0.001; Fig. 2). Moustached tamarins and saddle-back tamarins were found in mixed-species troops less than 45% of the time before 0600 h, but for more than 65% of the time at any other hour of the day. Degree of association was significantly higher in the second half of the activity period (after 1100 h) than in the first half (before 1100 h) (t = 4.56, df = 335, P < 0.001; for this analysis the times before 0600 h and after 1600 h were excluded). Time spent in association reached its maximum between 1400 and 1500 h when the two species were together in nearly 99% of all scans.

Degree of association varied between days. Minimally 23% and maximally 100% of the daily activity time were spent in association. A source of variation between days was the occurrence of intergroup encounters, i.e., encounters of the study group with neighbor groups. On days without such encounters, the species spent an average of 93% (SD: 7%; n = 14 days) of the time in association. In contrast, association time was 75% (SD: 21%; n = 20 days) on days with such encounters. The difference is statistically significant (t = 3.21, df = 32, P < 0.005).

Fig. 2. Frequency of association of Saguinus mystax and Saguinus fuscicollis during the day. Vertical lines within or above the bars indicate the standard deviation.

Social Interactions Between Species

A total of 112 interactions between moustached tamarins and saddle-back tamarins were observed (approximately 1 interaction/5 h of observation). Fifty-two percent of interspecific interactions occurred as isolated events; 48% were clumped in time; i.e.,.two or more interactions (maximum eight) were observed within a limited time (maximum I h) and within the same context.

Most interactions were agonistic (108/112), consisting of either an aggressive act (threat, attack, chase) or an avoidance. Moustached tamarins initiated 65 aggressive acts that were directed to a saddle-back tamarin. Further, all except one avoidance was by saddle-back tamarins going or running away on the approach of a moustached tamarin. Since in such situations subtle aggressive signals of the moustached tamarins may have evaded the observer's attention, aggression and avoidance were lumped together as a single category, "agonistic."

The majority of agonistic interactions occurred when the animals were feeding or stayed at a plant food resource (Table III). Most of these resources were small, i.e., they had a small crown diameter (< 5 m) and/or yielded only a small number of ripe fruits at a time (Table IV). Exudate feeding sites, where only some animals could feed simultaneously, and pods of "pashaco"-trees (Parkia sp., Leguminosae), the only fruits that were eaten on the ground, also have to be considered as small resources. Large food resources were trees or vines with a crown diameter of more than 5 m and/or a large number of ripe fruits. Agonistic interactions occurred rarely during other activities like foraging for animal prey, traveling, and resting.

Nonagonistic interactions between moustached and saddle-back tamarins were extremely rare. They comprised three play invitations directed by a saddle-back tamarin to a moustached tamarin, and a short episode when the female moustached tamarin sat in contact, perhaps casually, with the tail of a saddle-back tamarin. No interspecific social grooming was observed, although both species frequently rested close together. Since resting sites often are at heights of 20 m or more, observability is reduced and interspecific social grooming may have escaped the observer's attention.

TABLE III. Contexts of Interspecific Agonistic Interactions

| Activities |

%

|

n

|

| Feeding on plant food resource |

77.8

|

-84

|

| Foraging for animal prey |

4.6

|

-5

|

| Traveling |

1.9

|

-2

|

| Resting |

6.5

|

-7

|

| Undetermined |

9.3

|

-10

|

|

100

|

-108

|

TABLE IV. Characteristics of Food Resources

| Food resource |

%

|

n

|

| Small resourcea |

36.9

|

-31

|

| Large resourceb |

17.7

|

-15

|

| Exudate |

27.4

|

-23

|

| "Pashaco" pods on ground |

7.1

|

-6

|

| Undetermined |

10.7

|

-9

|

|

100

|

-84

|

'Crown diameter < 5 m and/or few fruits. bCrown diameter > 5 m and/or many fruits.

Time of Retirement and Distance Between Sleeping Sites

The association between moustached tamarins and saddle-back tamarins was highest between 1400 and 1500 h. Thereafter it decreased because the two species generally separated a short time before entering a sleeping tree. On 16 days the exact time of entering the sleeping site was determined for both species. The mean entering time was 1545 h ± 23 min for the moustached tamarin group and 1606 h ±30 min for the saddle-back tamarin group. The difference is statistically significant (t = -2.24, df = 30, P < 0.05). On only two occasions did the moustached tamarins enter their sleeping tree later than the saddle-back tamarins.

The distance between the sleeping trees of the two species was determined in 18 cases. On 2 days, moustached and saddle-back tamarins entered the same sleeping tree; on all other days different sleeping trees were used. Table V shows the distribution of distances between sleeping sites. The average distance was 33 m ± 26 m. This figure includes days on which the retirement to the sleeping trees was monitored by two observers, each focussing on one species, but also days on which only one observer was present. In the latter case, it may have been easier to observe the retirement of both species if they were using sleeping trees which were not too far apart. Therefore, the figure given above might underestimate the real distance between sleeping trees.

TABLE V. Distances between Sleeping Sites

of Saguinus mystax and

Saguinus fuscicollis

|

Distance class (m) |

No. of

observations

|

|

0a

|

2

|

|

1-20

|

3

|

|

21-40

|

8

|

|

41-60

|

3

|

|

61-80

|

-

|

|

81-100

|

2

|

a Both species in the same sleeping tree.

Mutual Calling

As stated above, the two tamarin.species generally

slept in separate sleeping trees. After leaving the sleeping trees in the early

morning between 0535 and 0628 h (Saguinus mystax, mean: 0603 h, SD: 12

min, n = 26 days), they joined each other on average within 20 min (SD: 31 min,

range: 0-151 min). One or more long calls were given by either of the two species

while still in the sleeping tree or shortly after leaving on 28 mornings, and

no long calling was heard on 11 mornings. The long calls were answered by the

other species on 14 mornings, and no reply was given on 14 mornings. It might

be hypothesized that the species for which the benefit of joining the other

species is higher should call first more often than the other species. However,

no significant difference was found in the frequency with which first calls

were given by moustached or saddle-back tamarins (X2 = 2.29, df = 1, P >

0.05).

The time that passed until the two species joined each other was influenced by the occurrence of long calling. When one or more long calls were given it took significantly longer for the two species to join than if no long call was given (U =40.50, Z = -2.62, P < 0.01). Time until joining was independent of which species called first (U = 37.00, Z = -0.85, P > 0.05) and also of whether an answer is given to the first long call(s) or not (U = 35.50, Z = -0.96, P > 0.05).

Of the 11 mornings on which no long calls were given, the two species had been sleeping in the same sleeping site on two mornings, the sleeping sites were less than 20 m apart on three mornings, and one species was already nearby the sleeping site of the other species on two other mornings. On the other three occasions the distance of the sleeping sites was not known, but judging from the time until the two species joined each other they must have slept rather close together.

Mutual calling by means of long calls also was observed when the two species became separated during.the day, especially after intergroup encounters. However, since such encounters generally were accompanied by a high level of long calling that may have continued even if the neighbor groups had already separated, it was impossible to distinguish long calls which were "addressed" to the neighbor group from those that were addressed to the association partner.